The University of Michigan

Periodical Cicada

Home Page

[What is a periodical cicada?] [Are periodical cicadas dangerous?] [Magicicada life cycles] [Magicicada broods (distribution maps)] [Magicicada behavior] [Magicicada species (with sound samples)] [Magicicada diseases and deformities] [Magicicada bibliography] [Other cicada links] [Meet us] [To contact us]

Cicadas are flying, plant-feeding insects of the Order Homoptera, which also contains groups such as the leafhoppers, aphids, and scale insects. Adult cicadas tend to be large (most are 25-50mm), and most North American species have clear wings, held rooflike over the abdomen. Cicadas have conspicuous long-range acoustic signals produced by specialized abdominal structures called tymbals; in most species only the males have these structures. Most cicadas are active only during the day and/or evening.

So far as is known, all cicadas have multiple-year life cycles (4-17 years). Cicadas in which almost all of the individuals in a given location mature into adults in the same year are periodical. Most cicada species are non-periodical, meaning that some adults are present in most or all years, while others show partial periodicity.

The most prominent and best-studied periodical cicadas are six species from eastern North America belonging to the genus Magicicada -- three species with 13-year life cycles, and three with 17-year cycles. The three 17-year species are generally northern in distribution, while the 13-year species are generally southern and midwestern. Magicicada are so synchronized developmentally that they are nearly absent as adults in the 12 or 16 years between emergences. When they do emerge after their long juvenile periods, they do so in huge numbers, forming much denser aggregations than those achieved by most other cicadas. Entomologists often use the common name periodical cicada to refer to this genus alone. Periodical cicadas are also known as "17-year locusts," but they are not locusts; locusts are a type of grasshopper.

Magicicada adults have black bodies and striking red eyes and wing veins, with a black "W" near the tips of the forewings. Most adults emerge in May and June, and live for only a few weeks. Certain other medium- to small-sized late spring and summer cicadas are sometimes mistaken for periodical cicadas, such as those in the genera Diceroprocta and Okanagana; these cicadas may be present May-July, may have black or orange coloration, and may also be somewhat periodical, though not as dramatically so as Magicicada. Other common North American cicadas include the large, greenish "dog-day" cicadas (genus Tibicen ) found throughout the U.S. in the summer. Non-periodical cicadas are often called "annual cicadas" (even though they have multiple-year life cycles) because in a given location adults can be found every year. For more information on the annual cicadas found in Michigan (with photographs and songs), see our Michigan Cicadas Page.

Female periodical cicadas (see picture below) have a pointed abdomen with an ovipositor for laying eggs. The ovipositor is sheathed and not clearly visible in these photographs.

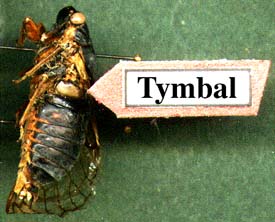

Males (below) have a blunter abdomen and white, ribbed tymbals located on the sides of the first abdominal segment, just behind the point of attachment of the hindwings. The lowest photo shows a male M. septendecim with wings removed to show the tymbal.

Are periodical cicadas dangerous?

Cicadas do not possess special defensive mechanisms -- they do not sting or bite. The ovipositor is used only for laying eggs and the mouthparts are used only for feeding on twigs; thus, periodical cicadas can hurt you only if they mistake you for a tree branch! When approached, a cicada will simply fly away. If handled, both males and females struggle to fly, and males make a loud defensive buzzing sound that may startle but is otherwise harmless. Cicadas are not poisonous or known to transmit disease.

Periodical cicadas can cause physical damage to small trees or shrubs if too many feed from the plant or lay eggs in its twigs; such damage can cause "flagging," or breaking of peripheral twigs. Orchard and nursery owners probably should not plant young trees or shrubs in the years preceding an emergence of periodical cicadas, because young trees may be harmed by severe flagging. Mature trees and shrubs, however, usually survive even dense emergences of cicadas without apparent distress. This can be difficult to believe in the month or so following a large emergence when many deciduous trees turn brown due to the breakage and death of peripheral twigs. As serious as it may appear, such damage is apparently minor. The simplest and possibly most effective way to protect small trees and shrubs is to physically prevent cicadas from feeding and ovipositing by covering the plants with screening material.

Other than the concern by owners of fruit orchards and nurseries, periodical cicadas are not regarded as pests, except maybe by those who tire of the din of their choruses.

Cicada juveniles are called "nymphs" and live underground, sucking root fluids for food. Periodical cicadas spend five juvenile stages in their underground burrows, and during their 13 or 17 years underground they grow from approximately the size of a small ant to nearly the size of an adult.

In the spring of their 13th or 17th year, a few weeks before emerging, the nymphs construct exit tunnels to the surface. These exits are visible as approximately 1/2 inch diameter holes, or as chimney-like mud "turrets" the nymphs sometimes construct over their holes. On the night of emergence, nymphs leave their burrows after sunset (usually), locate a suitable spot on nearby vegetation, and complete their final molt to adulthood. Shortly after ecdysis (molting) the new adults appear mostly white, but they darken quickly as the exoskeleton hardens. The cues that determine the particular night on which the nymphs emerge and molt are not well understood, but soil temperature probably plays an important role (Heath 1968). Sometimes a large proportion of the population emerges in one night. Newly-emerged cicadas spend roughly four to six days as "teneral" adults before they harden completely (possibly longer in cool weather); they do not begin adult behavior until this period of maturation is complete.

After their short teneral period, males begin producing species-specific calling songs and form aggregations (choruses) that are sexually attractive to females. Males in these choruses alternate bouts of singing with short flights until they locate receptive females. Contrary to popular belief, adults do feed by sucking plant fluids; adult cicadas will die if not provided with living woody vegetation on which to feed (see picture below of Magicicada septendecula feeding. The piercing-and-sucking mothparts are visible just behind the forelegs).

Mated females excavate a series of Y-shaped eggnests in living twigs and lay up to twenty eggs in each nest (Marlatt 1923). A female may lay as many as 600 eggs (Marlatt 1923). Below is a photograph of Magicicada eggnests.

After six to ten weeks, in midsummer, the eggs hatch and the new first-instar nymphs drop from the trees, burrow underground, locate a suitable rootlet for feeding, and begin their long 13- or 17-year development.

Why are there so many of them?

Periodical cicadas achieve astounding population densities, as high as 1.5 million per acre (Dybas 1969). Densities of tens to hundreds of thousands per acre are more common, but even this is far beyond the natural abundance of most other cicada species. Apparently because of their long life cycles and synchronous emergences, periodical cicadas escape natural population control by predators, even though everything from birds to spiders to snakes to dogs eat them opportunistically when they do appear. Magicicada population densities are so high that predators apparently eat their fill without significantly reducing the population (a phenomenon called "predator satiation"), and the predator populations cannot build up in response because the cicadas are available as food above ground only once every 13 or 17 years. Periodical cicadas do have a specialized fungal parasite (see the Magicicada diseases and deformities section), but its effects on Magicicada population density are not well understood. Individual periodical cicadas are slower, less flighty, and easier to capture than other cicadas, probably because the safety afforded by their great numbers means that the risks of predation for an individual are low. Explaining the evolution of such an unusual life strategy is one of the most difficult problems for periodical cicada biologists.

Magicicada broods and distributions

Although nearly all of the periodical cicadas in a given region emerge in the same year, the cicadas in different regions are not synchronized and may emerge in different years. All periodical cicadas of the same life cycle type that emerge in a given year are known collectively as a single "brood" (or "year-class"). The resulting broods are designated by Roman numerals -- there are 12 broods of 17-year cicadas (with the remaining five year-classes apparently containing no cicadas), and 3 broods of 13-year cicadas (with ten empty year-classes). As a result, it is possible to find adult periodical cicadas in almost any year by traveling to the appropriate location. The table below is a guide to the approximate locations of periodical cicada broods. On a local scale, periodical cicadas can be very patchily distributed.

Click here for a small-scale composite map of all brood ranges.

Click on a brood number in the table below to see a larger-scale map of that brood's range.

|

17-year Broods |

Year |

General region |

|||

|

1961 |

1978 |

1995 |

2012 |

VA, WVA |

|

|

1962 |

1979 |

1996 |

2013 |

CT, MD, NC, NJ, NY, PA, VA |

|

|

1963 |

1980 |

1997 |

2014 |

IA, IL, MO |

|

|

1964 |

1981 |

1998 |

2015 |

IA, KS, MO, NB, OK, TX |

|

|

1965 |

1982 |

1999 |

2016 |

OH, PA, VA, WVA |

|

|

1966 |

1983 |

2000 |

2017 |

GA, NC, SC |

|

|

1967 |

1984 |

2001 |

2018 |

NY |

|

|

1968 |

1985 |

2002 |

2019 |

OH, PA, WVA |

|

|

1952 |

1969 |

1986 |

2003 |

NC, VA, WVA |

|

|

1953 |

1970 |

1987 |

2004 |

DE, GA, IL, IN, KY, MD, MI, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, TN, VA, WVA |

|

|

1956 |

1973 |

1990 |

2007 |

IA, IL, IN, MI, WI |

|

|

1957 |

1974 |

1991 |

2008 |

KY, GA, IN, MA, MD, NC, NJ, NY, OH, PA, TN, VA, WVA |

|

|

13-year Broods |

|||||

|

1972 |

1985 |

1998 |

2011 |

AL, AR, GA, IN, IL, KY, LA, MO, MS, NC, OK, SC, TN, VA |

|

|

1975 |

1988 |

2001 |

2014 |

LA, MS |

|

|

1976 |

1989 |

2002 |

2015 |

AR, IL, IN, KY, LA, MO, MS, TN |

Note: Maps are based on a variety of published and unpublished sources, and are intended to give only approximate brood ranges. Consult published sources (e.g., Simon 1988, Marlatt 1923 or USDA reports) for more detailed information.

Sometimes periodical cicadas emerge "off-schedule" by one or more years. This phenomenon is often referred to by the general term "straggling," although straggling cicadas can emerge either later or earlier than expected. Straggling makes it difficult to construct accurate maps of periodical cicada brood distributions, and historical reports of emergences often contain little or no information about how many cicadas were seen. Straggling emergences in which one or two cicadas are present are common; larger unexpected emergences of thousands of individuals have been reported (e.g. Dybas 1969).

As in nearly all cicada species, male periodical cicadas produce "songs" using a pair of tymbals, or ridged membranes, found on the first abdominal segment. The abdomen of a male cicada is hollow and may act as a resonating chamber; the songs of individuals are loud, and large choruses can be virtually deafening. Female cicadas do not usually have sound-producing organs. Both sexes hear the sounds of the males as well as other sounds using membranous hearing organs called "tympana" found on the underside of the abdomen.

Over the course of an emergence, males congregate in "choruses" or singing aggregations, usually in high, sunlit branches. Females visit these aggregations and mate there, so choruses contain large numbers of both sexes.

Males of all Magicicada species (each described individually below in the "Magicicada species" section) produce alarm calls when handled, calling songs that attract males and females to the chorus, and one or more courtship calls when approaching and attempting to mate with females. Five different male acoustic signals have been described for the -decim and -cassini cognate species. Samples of most of these sounds are included below. These species have calling and courting signals that differ in pitch (frequency) and other characteristics, but the signals have have similar structures, so they can be described together. The functions of these signals are not entirely understood, but they have been given names to indicate their suspected function. The acoustical behaviors of the -decula species have not been as well characterized.

Male signals: (for recordings see the " Magicicada species" section)

Alarm Call: A rough buzz that males make when startled or handled; it is similar in pitch to the calling song, but coarser.

Calling song: Attracts both males and females to the chorus. Male -decim alternate bouts of calling (usually 1-3 calls) with short flights, while -cassini and -decula may make just one call between flights. The calls are approximately 1.5 - 3 seconds long in -decim and -cassini, and they are separated by silent gaps of about 1-2 seconds. The calling song of -decula is much longer, roughly 10-15 seconds in duration.

Court I (CI) Call: This signal is constructed of a series of phrases very similar to those used in the calling song, but more often without intervening bouts of flying or walking, and often with the gaps shortened. Males produce CI, CII, and CIII calls when courting a nearby female.

Court II (CII) Call: For -decim and -cassini, the phrases of this call are similar to those in CI calls. However, there are no gaps between call phrases, and the phrases may be shortened, or include an upslur. Males usually produce the CII call shortly before attempting to mount a female. The Court II call in -decula, if it exists as in the other two species, has not been well-characterized.

Court III (CIII) Call: This call consists of a continuous series of short, staccato buzzes, about 4-6 per second, in all three species. Males produce this signal while attempting to mount the female, stopping the sound only after engaging their genitalia.

Three 17-year cicada species exist, each with distinctive morphology, behavior, and calling signals. They are named below:

For each 17-year species, there is a morphologically and behaviorally similar species with a 13-year life cycle:

Magicicada tredecim (Walsh and Riley) - similar to M. septendecim

Magicicada tredecassini (Alexander and Moore) - similar to M. cassini

Magicicada tredecula (Alexander and Moore) - similar to M. septendecula

The closest relative of each Magicicada species appears to be a counterpart with the alternative life cycle, from which it can be distinguished only by life cycle and geographic distribution. For this reason, some biologists recognize only three Magicicada species, each with two different "life-cycle forms." Within each brood, two or three species with the same life cycle usually emerge together. The songs and morphology of the three 17-year species are described in detail below. For practical purposes, these can be used to identify 13- year species as well. The photographs below show, from left to right, dorsal and ventral views of a male, and dorsal and ventral views of a female. Each specimen is pinned through the thorax. The scale is a centimeter scale.

The largest of the periodical cicadas, with broad orange stripes on the underside of the abdomen, and with orange coloration on the sides of the thorax behind each eye and in front of the forewings (not visible in the photographs below, but partly visible in the M. septendecim tymbal photo above in the "What is a periodical cicada?" section). The calling song phrases are said to resemble the word "Pharaoh." Scale below is 1 cm long.

Magicicada septendecim songs:

|

Chorus (297K) |

|||

|

Calling song / Court I (132K) |

|||

|

Court II (88K fragment) |

|||

|

Court III (77K fragment) |

Usually smaller than M. septendecim. No orange coloration in front of the wing insertion behind the eye. Abdomen entirely black except in some locations where individuals may have weak ventral yellow-orange marks; if present, these tend to be faded and rarely form complete stripes. Sometimes such individuals may be difficult to distinguish from M. septendecula if calling song is not available. Calling song phrases consist of a series of ticks followed by a shrill buzz. Scale below is 1 cm long.

Magicicada cassini songs:

|

Chorus (septendecim in background, 297K) |

|||

|

Calling song / Court I (165K) |

|||

|

Court II (176K fragment) |

|||

|

Court III (154K fragment) |

Usually smaller than M. septendecim and similar to M. cassini in size, with narrow, well-defined orange stripes on the underside of the abdomen but no orange coloration in front of the wing insertion behind the eye. This species is often much more rare than M. septendecim and M. cassini. The calling song of the -decula sibling species is rhythmically unlike those of the other two forms, and consists of a series of short phrases lasting 15- 30 seconds. The first two courtship songs have not been well characterized, but may bear the same relationship to each other as the courtship songs of the other species. Scale below is 1 cm long.

Magicicada septendecula songs:

|

Chorus (mixed with cassini, 275K fragment) |

|||

|

Calling song (297K) |

|||

|

Possible Court II (?) (484K) |

|||

|

Court III (121K fragment) |

Magicicada diseases and deformities

Magicicada do not have any specialized predators, but periodical cicadas are subject to infection by the specialized fungal parasite Massospora cicadina Peck. During an emergence of periodical cicadas, both sexual and asexual forms of the fungus are present. Cicadas infected early in the emergence develop asexual spores, which become evident as the rear of the infected individual's abdomen breaks off, exposing a white, chalky mass of spores. This infection sterilizes the cicada but does not kill it immediately. These spores spread among the population, infecting other cicadas who will develop a secondary infection and whose abdomens will later break open, releasing sexual resting spores to infect the next generation of cicadas.

Cicadas sometimes fail to properly inflate their wings after molting; such individuals can be found in low vegatation in any emergence. There may be a tendency for this to occur more often in certain situations. The cicadas in the picture below came from a 1990 emergence in a suburban front yard near Chicago. Many of the cicadas in this area had deformed wings. Possible explanations include crowding (during molting) and use of lawn chemicals.

Molting can go wrong in other ways too. The cicadas in the picture below all failed to emerge completely from their nymphal skins. They died partially emerged.

Click here for a list of published scientific literature about periodical cicadas.

Click here for a list of published scientific literature about cicadas in general.

Email:

Visit our UMMZ Cicada page

Dan Century's Cicada Mania page has numerous links to other cicada sites

Search Chris Simon's online periodical cicada database at The University of Connecticut

All text, images, and sounds contained in or referenced by this page copyright John Cooley, David Marshall, and Mark O'Brien. No material from these pages may be duplicated or reproduced in any form without the written permission of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

Page maintained by John Cooley [email protected] and Dave Marshall [email protected] Last updated 8 January 2016

Keywords: periodical cicada, periodical cicadas, Magicicada, septendecim, cassini, septendecula, tredecassini, tredecula, tredecim, 17-year locust, 13-year locust, Homoptera, Cicadidae, Harvestfly.